UK Space Ambitions Clash With NATO Airspace Concerns

Via CityAM,

-

The UK’s new vertical launch spaceport at Saxa Vord poses risks to Icelandic airspace and territorial waters, potentially disrupting transatlantic flights and marine ecosystems.

-

Exclusion zones for rocket launches could interfere with NATO’s ability to effectively patrol the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom gap, an area of strategic importance for defense.

-

While a memorandum of understanding exists between the UK and Iceland, it may not adequately address the full defense and military ramifications of frequent space launches in this critical region.

When I relocated to the UK from New York in 1984, the Cold War was at its peak. US nuclear and conventional forces were spread across Europe and fears of a Soviet invasion or nuclear exchange were ever-present. In the UK, another critical strategic concern was the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) gap, which are two stretches of the North Atlantic separating these three countries. During the Cold War, Soviet naval forces aimed to control this gap to access the broader North Atlantic and block NATO reinforcements to Europe, a scenario famously depicted in Tom Clancy’s Red Storm Rising.

After the Cold War ended and the so-called Peace Dividend reduced the gap’s significance, its strategic importance faded. However, since 2014, with Russia’s renewed assertiveness, the GIUK gap has regained prominence in NATO planning. The US reopened Keflavik Naval Air Station in Iceland in 2016, re-established its 2nd Fleet in 2018 to protect the gap and, as recently as March 2025, Standing NATO Maritime Group 1 increased its patrols in the region.

I warn of danger

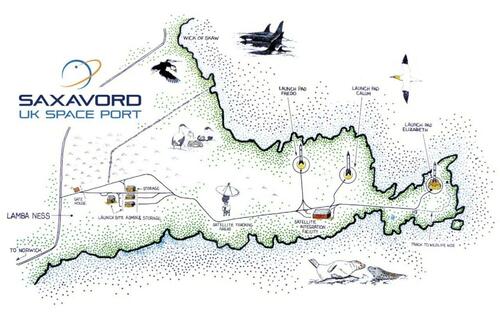

While NATO has prepared for Russian threats, a new risk closer to home is now emerging: the UK’s and Europe’s first vertical launch spaceport at Saxa Vord, Shetland. Ironically, this site was once an RAF early warning and air defence base during the Cold War, bearing the motto Praemoneo de Periculis, or “I warn of danger”.

Commercial space launches are still in their infancy, but recent incidents such as SpaceX’s launch failures – spreading debris across Florida and the Caribbean and grounding flights – and a Norwegian test rocket explosion highlight the risks. Saxa Vord itself attempted a rocket launch last August, resulting in an engine explosion. The international nature of space launches means that countries near Saxa Vord, especially Iceland, are directly in the path of up to 30 planned launches per year, four a month at peak, with ambitions to increase to 40 or 50 annually.

These launches pose multiple risks to Iceland and the GIUK gap:

-

Rockets may enter Icelandic airspace, with first-stage returns falling through Icelandic airspace and into territorial waters.

-

Catastrophic failures could scatter debris, whilst hazardous chemicals from rocket propellants threaten marine ecosystems.

-

Rerouted transatlantic flights of up to 76 a day, according to Icelandic air traffic control’s ‘anonymous’ response to the CAA’s Saxa Vord licence consultation.

-

Even more importantly and less scrutinised – the presence of exclusion zones for launches could undermine NATO’s ability to patrol the gap effectively.

Memorandum of Misunderstanding

These risks are partly managed by a memorandum of understanding (MoU) signed between the UK and Iceland in July 2021. The MoU mandates the closure of designated Icelandic sea and airspace areas before launches and outlines some procedures for debris recovery. However, while a handful of Icelandic officials are aware of the implications, the broader political and media discourse in both countries has yet to grapple with the full defence and military ramifications of the impact of such numbers of launches into NATO’s strategic sea and airspace.

The current trajectory of UK space ambitions – and planned rocket launch from the UK – means the UK’s space ambitions could inadvertently undermine the very security framework that underpins Western interests in the North Atlantic and the Arctic.

There is an urgent need for both the UK and Icelandic governments to reassess the risks from Saxa Vord, ensuring that existing bilateral agreements align the UK’s space programme with enduring geopolitical realities and the security needs of NATO and its allies. Saxa Vord has to be a success – but upon the present strategy security triumphs space whilst Iceland is developing its own space strategy – which might well consider how launch capability could be nationalised to give greater control over risk.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 05/21/2025 – 03:30